Book Publishing

Traditional Publishing

Self-Publishing

Electronic Publishing

POD & Subsidy Publishing

Promotion/Social Media

General Promotion Tips

Book Reviews

Press Releases

Blogging/Social Media

Author Websites

Media/Public Speaking

Booksignings

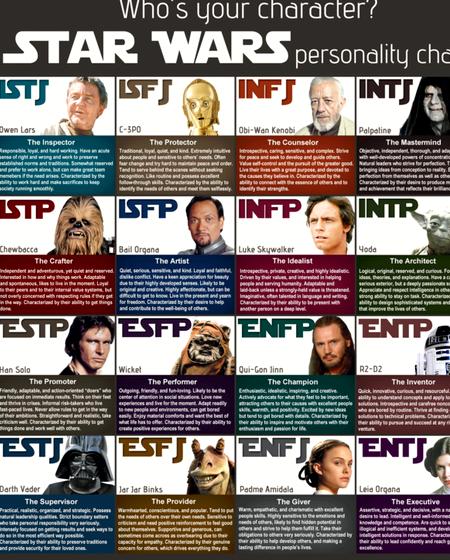

Your protagonist has a problem she needs to solve. How will she go about it? Maybe she’ll do it the same way you would if you were in her shoes. Then again, she’s not you, so maybe she’ll do it differently.

A character’s approach to problem solving, relationships, and crises can be mapped using the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. While no system should be used as a cookie-cutter to carve out characters in certain psychological shapes — the result would be characters as flat as cookies — you can use the fundamental dimensions of personality identified by Myers-Briggs to develop characters who come alive on the page.

These dimensions come in four pairs. An individual falls somewhere along a spectrum between the poles of each pair.

Following are thumbnail descriptions of each dimension. (For more detailed information, see the list of references at the end of this article.)

Extraversion (E) — Gets energy from people, activities, objects. Likes to interact.

Introversion (I) — Gets energy from ideas, emotions, impressions. Likes to concentrate.

Sensing (S) — Focuses on facts. Practical and proceeds step-by-step.

Intuition (N) — Focuses on possibilities. Theoretical and proceeds in leaps.

Thinking (T) — Makes decisions according to a logical system based on consistent principles. Believes in justice.

Feeling (F) — Makes decisions according to a value system based on a desire for harmony. Believes in compassion.

Judging (J) — Proceeds towards goals in an organized way.

Likes to make plans and come to decisions.

Perceiving (P) — Adapts to life in a spontaneous way. Likes to gather information and keep options open.

When using these terms, it’s important to remember that they have a Myers-Briggs meaning distinct from their meaning in everyday usage. For example, Ps are no more perceptive than Js, while Js are not necessarily judgemental. Ts are not unfeeling, and Fs are not unthinking.

Also, all of these dimensions indicate preferences, not abilities. For instance, two mages, one an E and one an I, could both study a difficult spell all day without talking to anyone or moving from their chairs, and they both could learn it. However, while the I might be so charged up by all that intense thinking that he’d need a drink to fall asleep, the E might feel exhausted and fall gladly into bed.

Let’s look at some famous fictional characters and analyze their Myers-Briggs types.

- Sherlock Holmes (ISTP). Content to live a solitary life or to socialize with a single roomate, Holmes is galvanized into action by problems that challenge his mind (I). Acutely aware of minor details in his environment, the detective repeatedly cautions that one must not theorize before having facts, and he solves puzzles by refining tried-and-true methods (S). His primary motivation, besides entertaining his brain with intricate puzzles, is to achieve justice (T). His rooms are a disorganized disaster area, and he fills his days with a variety of interests — scientific experiments, playing the violin, taking drugs — for as long as they are interesting (P).

From the above analysis, it’s evident that a character’s four Myers-Briggs dimensions interact with one another and with her life situation. The result is not one personality of a possible sixteen combinations but a unique personality in a universe of possibilities. How can Myers-Briggs Types be used to strengthen a story?

Pairing Characters

Opposites attract — and conflict. Felix and Oscar; Jeeves and Wooster; Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser; Spock and McCoy; Mulder and Scully. Having sparks fly between two strong characters makes a gripping story. An easy way to differentiate two characters is, for instance, to make one exuberant and the other withdrawn. However, just as in real life, superficial differences cause only superficial annoyances and interest. It takes fundamental differences to create real chemistry.

If you’re writing about a middle-aged, by-the-book cop who teams up with a drug dealer to fight some larger evil, don’t just make the drug dealer young and impudent. After digging a little deeper into the backgrounds and personalities of these characters, you might profile the cop as follows:

Alysha, who joined the force to help people and society in a hands-on way (E), is finally burning out, her enthusiasm dimmed by the realities (S) of the job, especially the violence she sees and the lack of appreciation she receives (F). She takes refuge from the daily assault on her emotions in the structure of the job: the uniform, the regulations, and the group norms of the force (J). Alysha is an ESFJ.

On the other hand, our drug dealer looks like this:

Highly imaginative but an unidentified dyslexic, Chris tuned out of school, preferably by staring out the window and making up stories in his head (I). By high school, he was cutting class to walk down the railroad tracks, smoking a joint and imagining where the steel road might lead (N). Although quiet, he enjoyed the company of other people and strived to make them happy, and for this reason he tended to be susceptible to peer pressure (F). Because he needed structure but couldn’t find it in school, he eagerly joined a gang (J). Also, he could see the entrepreneurial possibilities in controlled substance sales and quickly became a leader in “community business development” (N). Chris is an INFJ.

As Alysha and Chris work together, they will mesh well in some ways and clash in others. Both will favor a systematic approach to their investigation (J), and each will be concerned about the other’s emotional state (F). This sounds cosy but may lead to conflict. Given their different backgrounds, Alysha’s systematic approach probably differs from Chris’. As Js, they will both be loathe to bend to an unfamiliar way of working. Likewise, their sensitivity to each other’s feelings may mean they fail to communicate when what they have to say isn’t nice.

In addition, their different sources of energy may make it hard for them to work together. As an E Alysha may want to talk through a complicated situation to understand it, while as an I Chris would prefer to think it through in solitude. Chris may see Alysha as intrusive and distracting, while she may see him as withholding and aloof. Furthermore, Chris may perceive the S Alysha as too bogged down in detail to see the overall pattern, while Alysha may view the N Chris as sloppy and forgetful about the facts in front of him. Their challenge as partners will be to use one another’s different strengths, while learning to tolerate the weaknesses.

First we wrote mini-biographies of our characters, keeping in mind the Myers-Briggs Type pairs. Then we identified each character’s Myers-Briggs Type. Finally, we developed their relationship based on what we know about each one’s Type and how it is likely to interact with the other’s. You can take this process into much more detail than the above example, until your characters practically walk from the page and start talking to each other. Let’s take a look at some other ways to use Myers-Briggs Typing.

Finding a Vocation:

The quest for one’s true path in life is a common plotline of fantastic fiction. Katherine Kurtz’ priest Cinhil becomes a reluctant king; Anne McCaffrey’s vengeful scullery maid Lessa becomes a Weyrwoman; and Bruce Sterling’s wealthy hypochondriac Alex Unger discovers a passion for science. In real life, Myers-Briggs Typing is used to suggest possible career choices for people. Any Type can succeed at any career. However, some jobs may feel more comfortable than others, and someone may need to tackle some jobs in a consciously different way than most others to apply their strengths.

An ISTJ might fit comfortably into life in a monastery, copying manuscripts by the hour in painstaking detail. However, he wouldn’t particularly want to teach the concepts in the texts to other monks, and he would be intolerant of interruptions to his work. An ENFP might start a high-risk, interplanetary, import-export venture. If the venture was successful, however, she would never have much interest in the accounting side of the operation and might rapidly lose interest altogether in favor of a new project. “Taxes? Oh, taxes!” Explaining how your characters’ Types support the work they do (or explaining why they’re doing something for which they are tempermentally unsuited and, if successful at it, how they succeed) will build deeper, more consistent characters.

Responding to Authority:

Opposition to authority or “the system” is a staple of speculative fiction. In general the establishment is more likely to view Ps, with their hang-loose style and unwillingness to commit, as potentially seditious elements. However, unless pushed hard, many Ps are willing to do what it takes to get along. It’s the decisive, rigid Js who may be more likely to rebel, and when Js try to overthrow the system, they will have a plan.

Ts are more likely to be set off by something they see as unfair, while Fs are more likely to go into revolt over something that causes pain to someone they know. An S may confine himself to small acts with known outcomes, like sabotaging computer code to prevent rockets from being launched, while an N may envision overthrowing the world order to replace it with utopia. Es will usually work with other people, perhaps launching a populist movement, while Is will work alone, with a small group, or through a close group of advisors.

Making Decisions:

If your characters take an active role in shaping their destiny, then at some point in the story they will probably make an important decision. While a J may make this decision at the beginning of the story, then spend the rest of the story living (or dying) with the consequences, a P may delay to collect more information and change her mind several times. With a P as a protagonist, the story becomes about the investigation or deliberation leading up to the decision.

Ts will base their decision on abstract principles of what’s right or fair, while Fs will consider what will do the most good for people. Ss will work with data or observable facts, and their decision will address the current situation, whereas Ns will focus more on overall patterns and focus on future outcomes. An I may write in his journal before arriving at a decision, while an E would prefer to talk things through with friends.

Assigning a group of four letters to a character isn’t important by itself. It’s the process that’s useful, as well as the understanding that if a character acts like an F in one situation, then she should act like an F in the next, not like a T because the author needs to move the story a certain direction. If your characters are as true to Type as real people, your readers will care about them as if they were real.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator is based on Carl Jung’s theory of psychological functions, and it can be used in more complex ways than simply considering the four dimensions discussed here. For more information, here are some resources.

Find Out More.

Helpful Sites:

Center for Applications of Psychological Type, Inc. capt.org/

Previous answers to this question

This is a preview of an assignment submitted on our website by a student. If you need help with this question or any assignment help, click on the order button below and get started. We guarantee authentic, quality, 100% plagiarism free work or your money back.

Get The Answer

Get The Answer