The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was created in 1945 to ensure the stability of the international monetary system, the agency helps stabilize the global economic system by monitoring exchange rates and enabling countries to transact with one another fairly. Headquartered in Washington, D.C. the Fund has an almost global membership of 188 countries.

Writing for the Chicago Journal of International Law. in 2013, Associate at Law firm Fenwick West, Nicholas Plassaras stated that bitcoin posed no immediate threat for the IMF, but “as more and more people come to understand the advantages of digital money over paper money, the threat it poses becomes increasingly real.”

“If the future of e-commerce entails a transition to digital currencies, it is critical that our economic, political, and legal institutions are prepared. Recognizing the importance of Bitcoin in the context of digital currencies is the first step in understanding how to best plan for the future. Bitcoin and other digital currencies like it are projected to become important players in the future of ecommerce. The time to consider how to prepare for that future is now before practical problems arise.”

In November 2013, IMF communications department director Gerry Rice echoed this sentiment, stating that bitcoin was not an issue, but there were points surrounding it that should be watched.

“It raises a number of topics and issues including issues of regulation, issues of consumer protection. For the time being, it’s too limited a phenomenon to have any macroeconomic significance or financial stability implications, but again, something to watch.”

– Gerry Rice, IMF Communications Department Director

Just four months later, in February 2014, the managing director of the IMF, Christine Lagarde, appeared on the Australian TV show “QA,” where she called bitcoin “suspicious,” when answering a question about the lack of trust in the legacy banking system, and used the go to statement of the day, that bitcoin is “for money laundering.”

Madame Lagarde was appointed as the Managing Director of the IMF in July 2011. She was previously the French Finance Minister, starting in June 2007, and also served as France’s Minister for Foreign Trade for two years.

At a recent banking conference in New York, Lagarde reportedly spoke to bankers on the subject of Bitcoin. “Many of you in the industry are actually worried that [bitcoin and blockchain] technologies are going to massively disrupt the current industry,” she then urged bankers to “pause for a second.”

“If those new technologies, and as long as those new technologies are going to abuse, take advantage of, the yield for anonymity, I think the banking industry has quite a few good days ahead of it as long as it takes ownership of those issues of capital and culture in order to actually restore the trust without which you see no trade no transaction no business can take place.”

Madame Lagarde now calls the Blockchain “that unbelievable technology that underlies the Bitcoins of this world.” And contemplates “how incredibly convenient it will be to actually generate trust and identify players and whatever pseudo they decide to use.”

The IMF is clearly taking note of the digital currency as time moves on. Aside from the convenience that Lagarde now sees in bitcoins transparency, Plassaras thinks there is a more pressing issue that the IMF should be concerned with.

To facilitate the IMF’s main goal, ensuring the stability of the international monetary and financial system, the Fund maintains a currency reservoir. When joining the agency, each country is assigned an initial quota. based broadly on its relative position in the world economy.

Quotas are denominated in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). the IMF’s unit of account. The largest member of the IMF is the United States, with a current quota of SDR 42.1 billion (about US$59 billion), and the smallest member is Tuvalu, with a current quota of SDR 1.8 million (about US$2.5 million).

A member must pay its subscription in full upon joining the Fund. Up to 25 percent must be paid in SDRs, or widely accepted currencies including U.S. dollar, the euro, the yen, or the pound sterling, while the rest is paid in the member’s own currency.

The quota system allows the Fund to maintain a diverse stockpile of foreign currencies that can be loaned to countries in need of assistance.

“The IMF issues an international reserve asset known as Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) that can supplement the official reserves of member countries. Total allocations amount to about SDR 204 billion (some $286 billion).”

– International Monetary Fund

A core responsibility of the IMF is to provide loans to member countries. This financial assistance enables countries to rebuild their international reserves, stabilize their currencies, continue paying for imports, and restore conditions for strong economic growth, while undertaking policies to correct underlying problems.

The volume of loans provided by the IMF has fluctuated significantly over time. The oil shock of the 1970s and the debt crisis of the 1980s were both followed by sharp increases in IMF lending. In the 1990s, the transition process in Central and Eastern Europe and the crises in emerging market economies led to further surges of demand for IMF resources. Deep crises in Latin America and Turkey kept demand for IMF resources high in the early 2000s. IMF lending rose again in late 2008 in the wake of the global financial crisis.

Plassaras asserts that the IMF is ill-equipped to handle the widespread use of digital currencies in the foreign exchange market, and a theoretical speculative attack from bitcoin users.

A speculative attack in the foreign exchange market is the massive selling of a country’s currency assets by both domestic and foreign investors.

If this happens, the nation’s central bank would need to already possess bitcoin reserves in order to offset the attack, and if it does not have enough bitcoin, it would turn to the IMF for assistance, if it is a member.

However, the IMF does not have any bitcoin currently, and will find it challenging to obtain enough bitcoin for their reserves. Further, if there is a speculative attack by a bitcoin holder, the IMF’s current rules do not allow the agency to acquire bitcoin.

“The rules of the institution, contained in the IMF’s Articles of Agreement signed by all members, constitute a code of conduct. The code is simple: it requires members to allow their currency to be exchanged for foreign currencies freely and without restriction, to keep the IMF informed of changes they contemplate in financial and monetary policies that will affect fellow members’ economies, and, to the extent possible, to modify these policies on the advice of the IMF to accommodate the needs of the entire membership.”

– International Monetary Fund

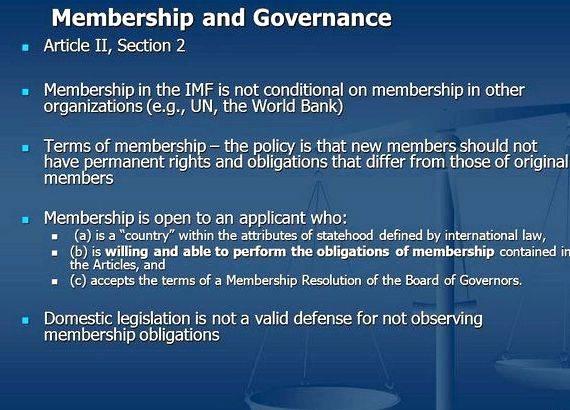

Since bitcoin is neither a nation-state nor does it have any centralized financial institution to do business with the IMF, Plassaras claims that the Articles of Agreement do not permit the agency to exercise direct control over the use of Bitcoins. Therefore, the agency would have to do something quite drastic, such as amending the Articles.

Based on Plassaras’ interpretation, there are only two ways which the IMF could ever acquire bitcoin.

The IMF could accumulate Bitcoins through its member countries by expanding the scope of Article IV, Section 5 of the Articles of Agreement to include digital currencies. This would enable the Fund to require all member nations to pay part of their subscription quota with bitcoins, giving the IMF a steady supply of bitcoins for their reserves. However, the rules can be interpreted loosely or strictly, and this may not be possible at all, he speculates.

Alternatively, the IMF can directly acquire bitcoins themselves, from exchanges and users. The problem is that “Article II, Section 2 explicitly states that membership to the IMF is only open to other countries,” Plassaras argues. Therefore, in order to obtain bitcoin directly, “Article II could be amended to include a new section, Section 3, which provides quasi-membership status for digital currencies.”

Since bitcoin would not need full IMF benefits or burdens of membership, such as the ability to borrow money from the IMF, the agency would “recognize Bitcoin as an ‘IMF-official’ digital currency.” Plassaras suggests that by this method, bitcoin will gain increased legitimacy from the IMF’s recognition, while the IMF would benefit from having a way to purchase bitcoin reserves.

Plassaras cautioned that there are practical challenges to the direct approach. For example, the IMF would need a large amount of bitcoins for its reserves, which could be difficult to obtain for anyone at the scale required.

Either way, for the IMF to ever be able to protect its member countries from speculative attack by bitcoin, it will find it nearly impossible to acquire all of the bitcoins it needs. To even attempt to do so would require them to start soon and keep constantly buying in order to not push the price up too much at any given time.

For now, Madame Lagarde seems to have little fear, since so few people believe that bitcoin the currency is going to achieve mainstream adoption. However, if it ever does so, then it will likely be too late for the agency to acquire enough bitcoin to do either job of defending against speculative attacks, and providing loans to distressed central banks.

Previous answers to this question

This is a preview of an assignment submitted on our website by a student. If you need help with this question or any assignment help, click on the order button below and get started. We guarantee authentic, quality, 100% plagiarism free work or your money back.

Get The Answer

Get The Answer