B.A. Gerrish is John Nuveen Professor Emeritus in the College of Chicago Divinity School and Distinguished Service Professor of Theology at Union Theological Seminary in Virginia. This short article made an appearance within the Christian Century, April 9, 1997, pp. 362-367. through the Christian Century Foundation utilized by permission. Current articles and subscription information are available at world wide web.christiancentury.org. This short article ready for Religion Online by Ted Winnie Brock.

The Review:

Feuerbach and also the Interpretation of faith. by Van A. Harvey. Cambridge College Press, 319 pp. $59.95.

Man’s nature, as they say, is really a perpetual factory of idols. —John Calvin

Based on the Hebrew scriptures, humans were created within the image and likeness of God. However the perceived kinship between deity and humanity applies only too readily to the potential of inversion. Let’s say the gods are human creations, fashioned following the image and likeness of humanity?

Around 500 B.C.E. the Greek philosopher Xenophanes observed the gods from the Ethiopians were black coupled with flat noses, whereas the gods from the Thracians were blond and blue-eyed. He recommended that oxen, lions and horses, when they might make gods, will make them like oxen, lions and horses. Not too he found no use for that perception of deity. But their own God was similar to mortals, he stated, neither fit nor in thought. He mocked the all-too-human gods around him with regard to a much better, purer idea of God. And thus did the Hebrews, though a philosopher like Xenophanes may think that they less success.

The God from the Hebrews, whoever likeness humanity was produced, insists, I’m God and never man, the Holy One out of your midst (Hos. 11:9).

The Hebrew scriptures are replete with scorn for that idolatry which makes gods within the likeness of humans. Isaiah would likely not have access to permitted the God of Israel, who sits over the circle of the world. [and] stretches the heavens just like a curtain (Is. 40:22), might exhibit exactly the same idolatrous principle because the heathen gods he despised, only within the milder type of a mental image. What he announced would be a busy, active God instead of a picture that won’t move. But he can just represent the divine activity as very similar to human activity.

The persuasion the gods from the heathen are idols (Ps. 96:5), as the true God is God and never human, was transported over in to the Christian community to affirm the sovereign uniqueness from the Christian deity. The Protestant Reformers, it is a fact, discovered the worst idolatries of inside the Catholic Church, almost as much ast the prophets of old accused the kids of Israel of whoring after other, questionnable gods but they didn’t doubt that Christianity alone worshiped the real God without taint of idolatry. Through the good reputation for the church, dangerous anthropomorphisms in Christian discourse were excused by attract the covered, analogical, symbolic or poetic type of the spiritual thought.

Modern critical considered religion came about once the fortunate position of Christian discourse was finally challenged. Within the 17 th and 18 th centuries, a distinction familiar in classical ancient times was elevated: the dividing line was attracted not between Christianity along with other religions, but between popular religion, including Christianity, along with a purely rational theism.

The rational theists desired to marvel in the orderly span of nature without worshiping it or assuming so that it is the game of the cosmic Thou, available to the influence of sacrifice and prayer. This left the way in which obvious for such early pioneers of spiritual psychology as John Trenchard to locate the supposed pathological origins of faith within the soul while still coming across along the side of God (correctly understood).

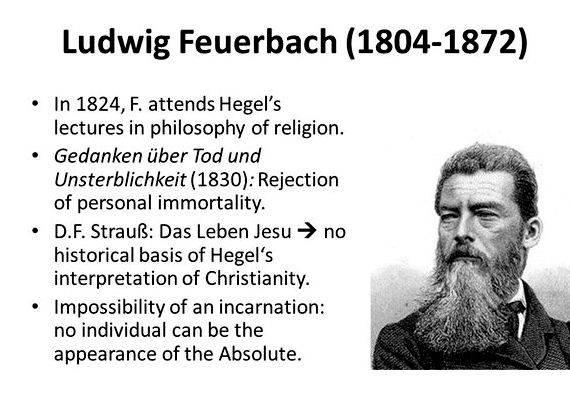

However in the German philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872) the privileging of Christian discourse and also the among vulgar religion and rational theism both dissolve, and all sorts of talk of God is unmasked because the product of human invention. At some point, he predicted, it will likely be globally recognized the objects of Christian religion, such as the questionnable gods, were mere imagination. And that he had no real interest in saving the absolutely unnecessary, unnecessary God, whose activity adds absolutely nothing to what the law states-governed processes of nature.

Van Harvey’s book may be the first volume inside a new series: Cambridge Studies in Religion and demanding Thought. The series could not happen to be launched with better auspices. Feuerbach and also the Interpretation of faith may be the ripe fruit of lengthy reflection. The timeliness—even the emergency—of its central real question is plain in the first chapter towards the last: Can religion be plausibly described with no assumption that God denotes a being of the greater ontological rank compared to mundane objects in our daily experience? Greater than 14 years’ labor entered the writing from the book, and also the author informs us that his preoccupation with Feuerbach dates back further still—to time as he first experienced him inside a graduate seminar at Yale Divinity School and located themself oddly disturbed.

Feuerbach established fact because the author of The Essence of Christianity. first printed the german language in 1841. (The 2nd edition was converted into British through the Victorian novelist George Eliot.) Harvey’s thesis is the fact that passion for that one work, intriguing and important although it is, has obscured a transfer of Feuerbach’s knowledge of religion that’s most apparent in the later Lectures around the Essence of faith (1848). We have to read Feuerbach for 2 interpretations of faith, not merely one, as well as in Harvey’s judgment the later, neglected interpretation is much more intriguing and persuasive. Not too a complete break occurs. Rather, the passage in the earlier towards the later writing is basically a shift of dominance: subordinate styles in The Essence of Christianity become dominant in The Essence of faith .

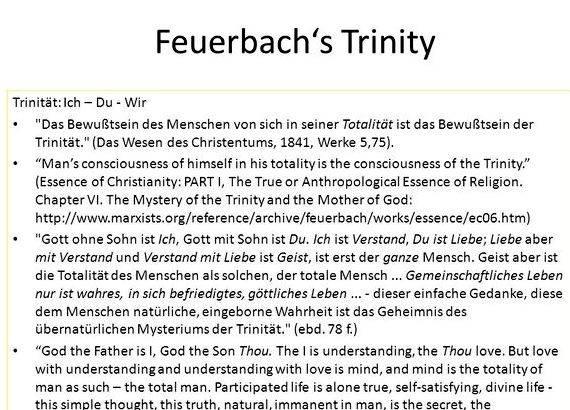

The central thought in The Essence of Christianity would be that the supposedly superhuman deities of faith are really the involuntary projections from the essential features of human instinct. In Feuerbach’s own words: Man—this may be the mystery of faith—projects his being into objectivity, and on the other hand makes themself an item for this forecasted picture of themself thus converted to a subject. Exactly what the devout mind worships as God is accordingly only the thought of a persons species imagined like a perfect individual. After they are unmasked, proven for which they are really, religious belief and the thought of God could be helpful instruments of human self-understanding, revealing to all of us our essential nature and price. But taken at face value, they’re alienating insofar because they betray us into placing our very own options outdoors people as features of God and never of humanity, viewing ourselves as not worthy objects of the forecasted image of the essential nature. Theology, as Feuerbach sees it, only reinforces the condition of alienation if you take the objectifications of faith legitimate objects, and also the theologians finish track of dogmas which are self-contradictory and absurd.

Very differently, The Essence of faith locates the subjective supply of religion in human reliance on nature. The forces of nature which our existence wholly depends are created less mysterious and much more pliable by our perceiving them as personal beings like ourselves. Which, we’re now told, may be the concept of religion, which isn’t a lot encoded truth as pure illusion. Nature, the truth is, isn’t a personal being it’s no heart, it’s blind and deaf towards the desires and complaints of individual. In a nutshell, religion is superstition, and science must eventually supplant it.

For the striking variations between Feuerbach’s two theories of faith, you will find strands that tie them together. One particular strand, clearly, may be the theme of anthropomorphism—picturing God or even the gods as personal like ourselves. Another, carefully associated with the very first in Feuerbach’s mind, may be the conviction that religion is unrealistic. Feuerbach’s felicity principle, as Harvey calls it, assumes that the purpose of being religious would be to secure one’s well-being both here and hereafter. Therefore, the emphasis within the later focus on the Glückseligkeitstrieb (the drive after happiness) that motivates the whole business of faith. The God we imagine may be the God we would like, who are able to provide us with what we should want, which means an individual God who takes notice people and guarantees us a blessedness that transcends the boundaries of nature. However that, based on Feuerbach, is the religious illusion (the expression is Harvey’s). We’re inescapably bounded through the limits of nature, as well as what we should require the goodness of God is simply the utility of nature personified.

Small question if budding theologians find valid reason in most this to become oddly disturbed! The unreflective believer may dismiss Feuerbach like a charlatan who trivializes religion. But Harvey fully vindicates his opinion that in almost any critical scrutiny of faith we have to grant Feuerbach a location alongside Paul Ricoeur’s masters of suspicion—Nietzsche, Marx and Freud—and judge him worthy to become introduced in to the present-day discussion. The final two chapters from the book set the later Feuerbach’s interpretation of faith within the forum more recent views of projection (Freud, Sierksma, Berger), anthropomorphism (Stewart Guthrie) and the requirement for illusion (Ernest Becker). Harvey concludes: It’s remarkable how good Feuerbach’s later views fully stand up in comparison with individuals of recent theorists so much in fact that you can, by adopting his position, mount important criticisms of those theories.

It’s aim, the writer informs us, is constructive, a minimum of partly. For this reason Feuerbach is introduced into the organization of latest religious theorists. Harvey doesn’t venture an organized statement of their own thoughts about religion. He writes as though listening to the conversation and notes what exactly where his Feuerbach, if there are any, might speak up. Historians who insist upon keeping past thinkers strictly in their own individual historic, social and intellectual contexts may raise their eye-eyebrows at this type of hazardous method. I, for just one, welcome it. Obviously, it can’t, as well as in this book it doesn’t, replace historic description and painstaking research into the sources. If your constructive conversation will be a genuine conversation, it must respect historic understanding and decide to try heart the historian’s warnings against anachronistic misreading from the sources. However a constructive interest previously (rational renovation, as Richard Rorty calls it) adds something towards the sober exercise of setting the record straight and might, occasionally, alert the historian to patterns bobs within the record that they had overlooked.

Harvey’s primary thesis is actually both historic and constructive. That the shift happened in Feuerbach’s ideas on religion, and just what it had been—these are factual matters. It appears in my experience to possess settled them (though I ought to defer towards the Feuerbach specialists). Why does Harvey think the shift marked a noticable difference within the more familiar projection theory in The Essence of Christianity. Exactly why is the later theory to become preferred? Chiefly for 2 reasons: first, it’s unencumbered through the arcane Hegelian speculation which case study of awareness rests in The Essence ofChristianity second, it will greater justice towards the religious feeling of encounter by having an other. Another factor to consider brings less comfort towards the believer compared to first. It’s one factor to become liberated from Hegel, another to become told the other experienced in religion is nature. However the conversation, remember, is all about academic theories of faith.

Initially glance, Feuerbach’s later theory appears like an elaboration of the view which goes back a minimum of towards the Roman poet Statius and it was elevated by Spinoza, Hobbes, Hume yet others: that anxiety about the terrifying forces of nature first produced the gods—within the ignorance of causes, as Hobbes explains. (Even Feuerbach’s Glückseligkeitstrieb appears to echo Hume’s anxious concern for happiness.) In fact, Feuerbach made themself the critic of the view. A persons encounter with nature is way too ambiguous and sophisticated to become subsumed underneath the single emotion of fear. It offers pleasure, gratitude and love, which, Feuerbach deduced, should also be makers of divinity. And that he thought that when we seek one all-embracing term for that full-range of spiritual feelings, we’ll think it is only within the sense of dependence, which each religious reaction to nature is, to say, a concrete individuation: anxiety about dying, gloom once the weather conditions are bad, pleasure when it’s good and so forth.

The merit of Feuerbach’s theory in the own eyes, and clearly and in Harvey’s, was it place a determinate concept, nature, instead of the vague, mystical word God. But was he right about religion? More modestly: So how exactly does his situation look in the outlook during the historic and systematic theologian?

Soon after publication of The Essence of Christianity. Feuerbach adopted a venerable German custom and began to show he was just saying what Martin Luther had stated already. (Luther’s name continues to be invoked in Germany to endorse an impressive number of mutually incompatible causes.) In The Essence of Belief Based on Luther (1844), apparently , the felicity principle is certainly not apart from Luther’s celebrated pro me (for me personally). For men must think that God is God only with regard to his blessedness. It’s the trust and belief from the heart that induce both God as well as an idol. And so forth. With a large number of Quotes from Luther, Feuerbach tells their own satisfaction that self-love—egoism, narcissism—motivates Protestant piety, which the piety itself produces the God it wants and needs.

To be certain, a significant Luther scholar will desire to say a little more concerning the purpose of the pro me in Luther’s theology and can explain some complicating counter evidence. The youthful Luther departed in the Augustinian tradition in using the words You will love your neighbor as yourself to forbid self-love, that they recognized as the main crime. The mature Luther stated that he understood his theology to be real since it takes us from ourselves. And thus we may continue. However when all is stated and done, is it feasible that Feuerbach were built with a point?

It’s, obviously, not Luther but Friedrich Schleiermacher who one thinks of when Feuerbach talks about religion because the sense of dependence. Feuerbach themself helps make the connection. But Schleiermacher really anticipated the naturalistic decrease in the religious sense of dependence and rejected it as being a misunderstanding. Our understanding of God is a sense of absolute dependence, whereas our reliance on nature is qualified by our capability to influence how a world goes. A very questionable distinction, because the process theologians prefer to help remind us. However the conversation isn’t yet closed.

Karl Barth doubted whether Schleiermacher had any defense against a Feuerbachian decrease in theology to anthropology: he thought that Feuerbach just demonstrated the planet what Schleiermacher had already completed to the queen from the sciences. In the own way, Barth loved Feuerbach. (A lot of us first discovered him from Barth.) But Barth came Feuerbach’s fangs by treating The Essence of Christianity simply like a critique of bad religion. For Barth the term bad, as it happens, is redundant: all religion may be the fruitless human pursuit of God. The Christian theologian is worried avoid religion but instead with thought—the Word of God. From Barth’s point of view, then, Feuerbach gave us nothing to bother with. From Feuerbach’s perspective, however, Barth’s countermove would be a relapse into premodern privileging of Christian discourse. Why don’t let presuppose in the start the a word of God is Jesus?

Personally, I believe Christian theology must face Feuerbach’s relentless exposure from the subjective roots of faith—even worry just a little about this. To be certain, the unmasking of narcissistic motives to be religious, although it may weaken the structures of plausibility, affords no logical cause for an inference about a realistic look at the religious object. The God one want to exist may really exist, whether or not the proven fact that one wishes it encourages suspicion. Nevertheless, within our consumer society, by which success within the church, as elsewhere, should really require market analysis of the items people want, the mechanism of unrealistic is one thing the theologian must hold constantly before us. The same is true the preacher, who’s pressurized to not prophesy what’s right but to talk smooth things, to prophesy illusions (Isa. 30:10). The issue remains if the only alternative for that theologian and also the preacher would be to offer another illusion.

Feuerbach would be a good listener, and Harvey is really a effective spokesman for him. But Feuerbach’s theories are more effective with particular sorts of religious experience compared to others. You will find religions of adjustment. once we might give them a call, that begin avoid the felicity principle however with the truth principle and admonish us to regulate our way of life towards the brute proven fact that situations are less we wish these to be. Feuerbach was too good an interpreter of faith to miss the phenomenon of self-abnegation, that they read like a subtle type of self-love. It’s no doubt correct that in adjustment to reality you might find peace, but surely the course of self-love here looks suspiciously just like a procrustean bed. In the remarks on Ernest Becker, Harvey themself hints that Feuerbach didn’t do justice to participatory religions of self-surrender.

Feuerbach’s theories also appear in my experience to operate badly with religions of ethicaldemand. (We will need to leave for an additional day the issue whether Émile Durkheim’s theory works much better.) Feuerbach was believing that religious belief corrupts morality in addition to reliability, and that he may even say: It is based on the character of belief that it’s indifferent to moral responsibilities. Well, some belief possibly! However the purpose of religion has sometimes visited counter human desires, wishes and self-seeking having a moral demand. It could possibly be just easy to one-up the resourcefulness from the theologians and show the way the existence of Mother Teresa, say, that has every appearance to be motivated by an impressive empathy rooted in religious conviction, has really been driven with a subtle but irresistible Glückseligkeitstrieb. However it strains our credulity less to understand evidence in her own existence of the close bond between (some) religion and (some) morality.

It might be too cheap to summarize that Feuerbach’s religious illusion ended up being to take one type of Protestant piety for religion itself. Still, unless of course there’s more to become stated than Harvey has told us, Feuerbach’s account must strike us as lopsided and incomplete. An explanation of faith don’t have to be eliminated simply because this is the religion at face value or continue with the first-order utterances from the believer. That will disqualify not just the masters of suspicion but many of theologians too, myself incorporated. The exam is whether or not the reason is sufficient fully selection of the utterances (or phenomena) it promises to explain.

Feuerbach claimed with a few justice that, unlike the speculative philosophers, he let religion speak by itself. However, it’s hardly surprising he heard best what came nearest by. Stung through the critique he offered an interpretation of Christianity being an interpretation of faith, he moved from The Essence of Christianity to The Essence of faith and, later, to his Theogony Based on the Causes of Classical, Hebraic, andChristian Ancient times (1857). But, throughout each one of these major works there appears to linger the influence of the strong dislike for Protestant pietism, which in fact had made an appearance already in the Ideas on Dying and Growing old (1830). In pietism, he supposed, each individual in the individuality grew to become the middle of their own attention.

This really is in no way to summarize that i’m completed with Feuerbach because, like average folks, he heard selectively. Rather, as Harvey concludes, he still has the ability to compel us to define our very own positions. Without qualifying like a Feuerbach scholar, I’ve discovered myself coming back over and over, like Harvey, for this devout atheist (as Max Stirner calls him), fascinated with the richness, tenacity and nettling type of his ideas on religion.

The choices, anyway, have grown to be clearer in my experience. Revisit our reason for departure: Christian anthropomorphism might be wholly imaginary, the reification of mere abstractions or perhaps a misconstrual of natural and organic phenomena or perhaps an imperfect symbolization in our encounter having a transcendent reality. Feuerbach themself moved from the first one to the 2nd option. Things I take is the gap in the later position provides me with some leverage around the third option. The transcendent the truth is felt by the religious imagination like a commanding will might be conceptually problematic. But there’s surely more into it than personification of some facet of physical nature. A far more nearly sufficient theory of faith, or anyway from the Christian religion, will need to provide a better account from it.

Viewed 28416 occasions.

Previous answers to this question

This is a preview of an assignment submitted on our website by a student. If you need help with this question or any assignment help, click on the order button below and get started. We guarantee authentic, quality, 100% plagiarism free work or your money back.

Get The Answer

Get The Answer